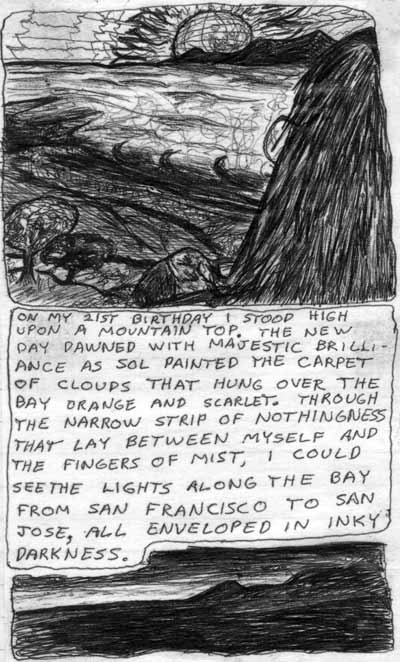

Rik

Rik

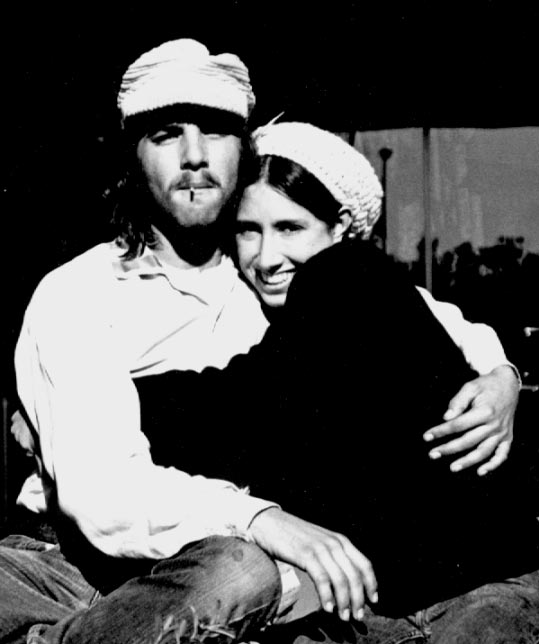

| Rik 'n Che: Chasing the Almighty Dollar in the Spring of 1970 Photo: ML Rocha used by permission |

Rik 'n Che on the long, winding road to The Land

When I was a little kid, my vision of glory, my fulfillment of adulthood, was to be the last man standing in the machine gun nest when the enemy stormed the hill. I wanted to excel. I wanted to exceed expectations. I wanted to be the American Hero. I would kill them all.

Nobody ever told me about the Korean War. Not even in school. It was as if it had never happened.

But they never stopped talking about World War II.

|

|

|

I never heard President Eisenhower say this. I was just a little kid. Little kids don't care about big people stuff.

But it doesn't appear that any big people listened to him him, either.

What's the old saying? Money talks, bullshit walks. President Eisenhower walked and the big money took over.

I was watching Pete 'n Gladys with my little sister when President Kennedy got shot. We were horrified. We hadn't been told that that kind of thing could happen in America. We loved President Kennedy. He was handsome. His wife was pretty. He was my hero because he shot rockets into space. Presidents made the world better. That's what Americans did. Why would anybody shoot him? That person must have been a bad, bad man.

They showed the vice president take the presidential oath, standing with the pretty lady who was President Kennedy's wife. They were on an airplane. She looked so sad. My sister and I cried. It was the first time we saw A REAL BAD THING happen.

Then the bad, bad man got shot on TV. They showed it over and over. The guy stuck a gun in his belly and pulled the trigger. He opened his mouth like it really hurt, and tucked in his arms and fell.

"That's what you get, you bad, bad man," I thought. I was glad. He deserved it. He deserved any awful thing.

They caught the man who shot him. I thought they should let him go.

"He was just doing what anybody else would do," I thought. Like John Wayne. John Wayne would have done that. Shot the bad, bad man...

|

|

But John Wayne would have shot him from the other side of the street. With a rifle. From the dark.

That's what you did when democracy didn't wok.

It was a beautiful thing.

It always brought a lump to my throat.

It didn't occur to me that that was exactly what Lee Harvey Oswald had done.

I was 13.

|

|

|

I never heard Joan Baez sing.

Well, I did but I never listened. I was into rock and roll. I liked Steppenwolf. The closest I ever got to folk music was Johnny Horton.

And I never heard Dr. Martin Luther King speak. In my home, in the white California neighborhoods where I grew up, a black man leading crowds of black folk and speaking loudly was regarded as a dangerous man. I wasn't sure why. But he was dead before I started thinking about the War. Shot by some redneck in the South.

Sure, it was wrong. But everybody was getting shot down there in the South. I was glad I was in California where my skateboard's wheels were made from crushed walnut shells and the teenie-boppers wore short shorts in the summer time.

The Vietnam War just went on and on and on. All through high school, it was as close as the new color television in the living room but as far away as the other side of the world. Freshman year. Sophomore. Junior. Senior year. I was studying. I was chasing girls. Girls were like magic. But they were hard to catch. Like wildebeasts!

I was building hot rods. Hot rods I could understand. Girls and why the army couldn't win a stupid little war in a backwater jungle - those were mysteries.

And the war itself? That was another mystery. But I was sure it wouldn't affect me. It would be over soon. Christ, it had already been going on longer than World War II. How could we have destroyed Germany and Japan and not be able to pulverize a bunch of evil commies who wanted to collapse the Asian countries like dominoes? That would be terrible. At least, that's what they said on TV.

But it didn't end. It just kept grinding along. One day, in my senior year, something clicked and I realized the Vietnam War was nothing but a jobs program. A meatgrinder. People were getting rich off it. They had found a way to turn helpless human beings into mountains of cash by blowing them up.

We weren't trying to win. The Arsenal of Democracy needed an enemy. We needed Russia and China to send their side more weapons so we could send our side more weapons. Build, sell, buy, send, kill, blow up. Build, sell, buy, send, kill, blow up. Bombs and bullets were like food. You always needed more the next day.

And look at all the people over there. Millions of pissed-off rice farmers clammoring for AK-47s. We could never kill them all. What a deal!

War was big business. Victory was the last thing the Arsenal of Democracy wanted. That would put an end to profit.

That sent a chill through my spine.

Everything was a lie.

The War was going to last forever...

I started listening to the folk singers.

I was 17.

|

|

| ||

|

Early in 1970, my Sociology professor pulled me aside and said, "Rik, you'd better be careful about what you say." |

I might be just a kid but I wasn't stupid. They were going to make me their slave, to fight, and maybe die, for their imperial profit. I was hurt. How could our parents' generation do this to us? Why hadn't they paid attention? They had raised us, their sons, for this? No wonder Jerry Rubin was telling us to kill our parents. (Unthinkable - but I finally saw where that distasteful radical was coming from.)

I was thouroghly outraged. I didn't have a country. I had lost my country! Someone, something, had taken it from me. I wanted it back. I wanted revenge. It was either run or stay and fight. But I knew how that would end up. Me, riddled with bullets or rotting in prison...

There was no solution. Only a short list of bad choices.

I needed to escape. I needed to figure this out. Everything I had been taught was, obviously, bullshit. I needed to wind back down to zero and start over.

And there was one more thing I needed to know. A burning question that kept surfacing in my sea of paranoia.

How did Richard Farina really die?

I was 19.

So I bought an old Chevy van with what was left of my semester savings and disappeared from the face of the Earth, heading north on a slow, winding, almost aimless trip towards Canada with my new Doberman pup and a couple of like-minded friends, Bruce and Cindy. But when I reached the Bay, something made me stop by the Institute for the Study of Non-Violence to see what it was all about. I didn't care about non-violence so much, whatever it was. But Joan Baez had finally captivated me with her voice and with her lyrics. There was something there that pulled at my heart - her compassion, her understanding, her mistreatment by the governent, her loss of a husband to prison for refusing to kill - and of course, her beautiful, plaintive, unforgettable voice.

I felt for her. I had nothing to offer. I just wanted a closer look.

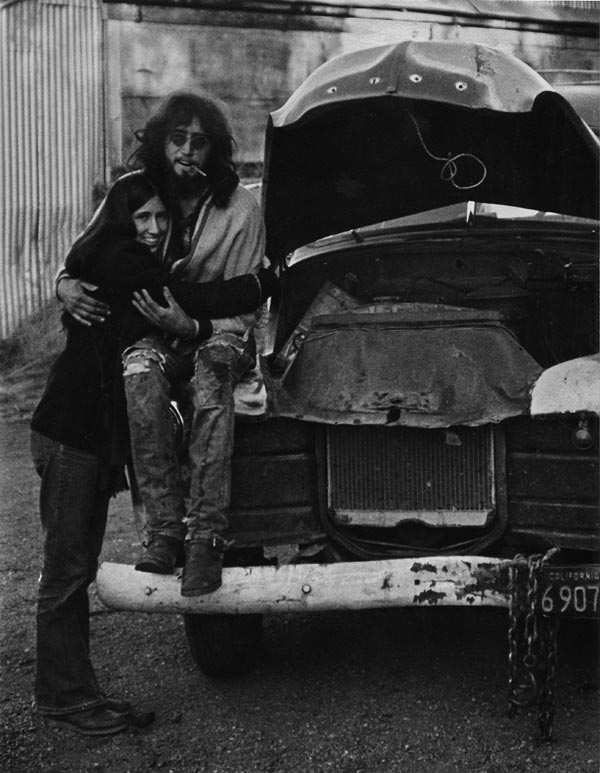

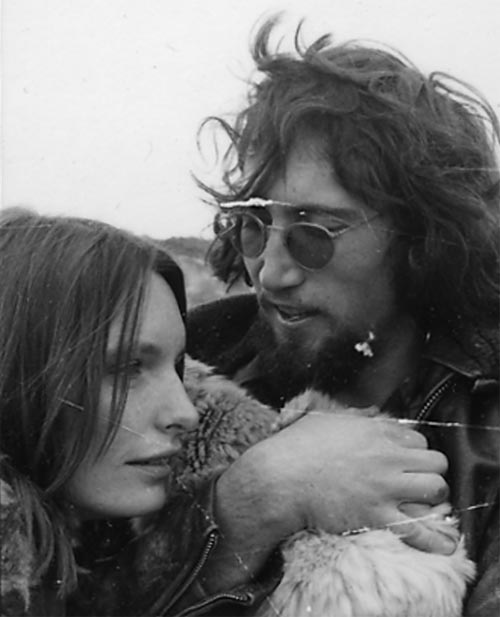

| Rik 'n Che in the Chevy van Photo: ML Rocha used by permission |

Non-violence was a new concept for me. The first time I learned about Ghandi was right there in the Institute's library at the Lytton House. He fought the entire British army with open palms and won. So there was another way...

I laid some cobblestones in the driveway for Joan. Some guy was there with a guitar, trying to sell her a stupid song, playing it through the window. "Man," I thought, "you just don't get it."

I found myself invited to a seminar at the Mountain House. These people had a plan. They weren't running and they weren't giving in. I was intrigued. Then something clicked. I decided to stay.

I really, really freaked them out when they found me cleaning my shotgun on the patio.

"I'll get a better price for it if it's pretty," I said, slipping the freshly-oiled 20-gauge back into it's case. Non-violence was going to be a brand new thing for me.

And it was funny. It was as if a terrible weight had been lifted from my shoulders. I had traded a futile, insignificant, loud weapon - a weapon the domestic foe could easily deal with - for a much more powerful, encompassing and quiet weapon that they had no hope of ever understanding. I would present them with the confusing quandry of the unarmed objector, the passive resistor, the grain of sand in the gears of the machine.

"First they laugh at you,

then they ignore you,

then they fight with you,

then you win." -- Ghandi

If I was to be ground to dust, at least I wanted to accomplish something.

Sand in gears I understood.

Then the transmission exploded on my truck.

I guess it wanted to stay, too. But Will and Janis needed the parking space, so they had someone tow it up to this place past Struggle Mountain they'd been talking about.

"The Land", they called it. An old ranch.

We pushed my van into the bushes and trees. It kind of blended in.

They drove off and left us there, me 'n Che. I crawled in the back of the panel with Che. It was freezing. Good thing he was so warm!

No food. No money. No wheels.

"Christ," I thought. "I'm gonna die up here!"

We heard the rumors trickling back from the War.

From vets, from soldiers on leave, from field medics, from the wounded - but mostly from the deserters who passed through the Institute, the Resistance or The Land. Stories often passed from one person to another, to another... Most common were the unending stories of killing children by accident - almost never officially admitted. After what we were hearing was done at Mai Li, we didn't doubt any of them.

The horror of warfare is a double-edged sword. It cuts the innocent as well as the guilty. Stepping across that white line at the induction center to serve the souless weapons makers, amoral oil corporations and the evil politicians they owned was one's final act of self - an act less than patirotism, more than fatalism, less than duty, worse than surrender, more than gullibility or the now incredible excuse of ignorance.

It was the first step of willingly rendering one's soul into offal.

|

|

"But I'm not givin' in an inch to fear Because I promised myself this year. No, I feel like I owe it to someone..." -- Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young | ||

| The Kent State Massacre -- America Turns on its Children | |||

| from The May 4 Shootings at Kent State University: The Search for Historical Accuracy by Jerry M. Lewis and Thomas R. Hensley Kent State Public Domain ...The decision to bring the Ohio National Guard onto the Kent State University campus was directly related to decisions regarding American involvement in the Vietnam War. Richard Nixon was elected president of the United States in 1968 based in part on his promise to bring an end to the war in Vietnam. During the first year of Nixon's presidency, America's involvement in the war appeared to be winding down. In late April of 1970, however, the United States invaded Cambodia and widened the Vietnam War. This decision was announced on national television and radio on April 30, l970 by President Nixon, who stated that the invasion of Cambodia was designed to attack the headquarters of the Viet Cong, which had been using Cambodian territory as a sanctuary. May 1, 1970 Protests occurred the next day, Friday, May 1, across United States college campuses where anti-war sentiment ran high. At Kent State University, an anti-war rally was held at noon on the Commons, a large, grassy area in the middle of campus which had traditionally been the site for various types of rallies and demonstrations. Fiery speeches against the war and the Nixon administration were given, a copy of the Constitution was buried to symbolize the murder of the Constitution because Congress had never declared war, and another rally was called for noon on Monday, May 4. Friday evening in downtown Kent began peacefully with the usual socializing in the bars, but events quickly escalated into a violent confrontation between protestors and local police. The exact causes of the disturbance are still the subject of debate, but bonfires were built in the streets of downtown Kent, cars were stopped, police cars were hit with bottles, and some store windows were broken. The entire Kent police force was called to duty as well as officers from the county and surrounding communities. Kent Mayor Leroy Satrom declared a state of emergency, called Governor James Rhodes' office to seek assistance, and ordered all of the bars closed. The decision to close the bars early increased the size of the angry crowd. Police eventually succeeded in using tear gas to disperse the crowd from downtown, forcing them to move several blocks back to the campus. May 2, 1970 As the Guard arrived in Kent at about 10 p.m., they encountered a tumultuous scene. The wooden ROTC building adjacent to the Commons was ablaze and would eventually burn to the ground that evening, with well over 1000 demonstrators surrounding the building. Controversy continues to exist regarding who was responsible for setting fire to the ROTC building, but radical protestors were assumed to be responsible because of their actions in interfering with the efforts of firemen to extinguish the fire as well as cheering the burning of the building. Confrontations between Guardsmen and demonstrators continued into the night, with tear gas filling the campus and numerous arrests being made. May 3, 1970 Nearly 1000 Ohio National Guardsmen occupied the campus, making it appear like a military war zone. The day was warm and sunny, however, and students frequently talked amicably with Guardsmen. Ohio Governor James Rhodes flew to Kent on Sunday morning, and his mood was anything but calm. At a press conference, he issued a provocative statement calling campus protestors the worst type of people in America and stating that every force of law would be used to deal with them. Rhodes also indicated that he would seek a court order declaring a state of emergency. This was never done, but the widespread assumption among both Guard and University officials was that a state of martial law was being declared in which control of the campus resided with the Guard rather than University leaders and all rallies were banned. Further confrontations between protestors and guardsmen occurred Sunday evening, and once again rocks, tear gas, and arrests characterized a tense campus. May 4, 1970 Although University officials had attempted on the morning of May 4 to inform the campus that the rally was prohibited, a crowd began to gather beginning as early as 11 a.m. By noon, the entire Commons area contained approximately 3000 people. Although estimates are inexact, probably about 500 core demonstrators were gathered around the Victory Bell at one end of the Commons, another 1000 people were "cheerleaders" supporting the active demonstrators, and an additional 1500 people were spectators standing around the perimeter of the Commons. Across the Commons at the burned-out ROTC building stood about 100 Ohio National Guardsmen carrying lethal M-1 military rifles. Conflicting evidence exists regarding who was responsible for the decision to ban the noon rally of May 4th. ...The decision to ban the rally can most accurately be traced to Governor Rhodes' statements on Sunday, May 3 when he stated that he would be seeking a state of emergency declaration from the courts. Although he never did this, all officials -- Guard, University, Kent -- assumed that the Guard was now in charge of the campus and that all rallies were illegal. Thus, University leaders printed and distributed on Monday morning 12,000 leaflets indicating that all rallies, including the May 4th rally scheduled for noon, were prohibited as long as the Guard was in control of the campus. Shortly before noon, General Canterbury made the decision to order the demonstrators to disperse. A Kent State police officer standing by the Guard made an announcement using a bullhorn. When this had no effect, the officer was placed in a jeep along with several Guardsmen and driven across the Commons to tell the protestors that the rally was banned and that they must disperse. This was met with angry shouting and rocks, and the jeep retreated. Canterbury then ordered his men to load and lock their weapons, tear gas canisters were fired into the crowd around the Victory Bell, and the Guard began to march across the Commons to disperse the rally. The protestors moved up a steep hill, known as Blanket Hill, and then down the other side of the hill onto the Prentice Hall parking lot as well as an adjoining practice football field. Most of the Guardsmen followed the students directly and soon found themselves somewhat trapped on the practice football field because it was surrounded by a fence. Yelling and rock throwing reached a peak as the Guard remained on the field for about ten minutes. Several Guardsmen could be seen huddling together, and some Guardsmen knelt and pointed their guns, but no weapons were shot at this time. The Guard then began retracing their steps from the practice football field back up Blanket Hill. As they arrived at the top of the hill, twenty-eight of the more than seventy Guardsmen turned suddenly and fired their rifles and pistols. Many guardsmen fired into the air or the ground. However, a small portion fired directly into the crowd. Altogether between 61 and 67 shots were fired in a 13 second period. Four Kent State students died as a result of the firing by the Guard. The closest student was Jeffrey Miller, who was shot in the mouth while standing in an access road leading into the Prentice Hall parking lot, a distance of approximately 270 feet from the Guard. Allison Krause was in the Prentice Hall parking lot; she was 330 feet from the Guardsmen and was shot in the left side of her body. William Schroeder was 390 feet from the Guard in the Prentice Hall parking lot when he was shot in the left side of his back. Sandra Scheuer was also about 390 feet from the Guard in the Prentice Hall parking lot when a bullet pierced the left front side of her neck. Nine Kent State students were wounded in the 13 second fusillade. Most of the students were in the Prentice Hall parking lot, but a few were on the Blanket Hill area. Joseph Lewis was the student closest to the Guard at a distance of about sixty feet; he was standing still with his middle finger extended when bullets struck him in the right abdomen and left lower leg. Thomas Grace was also approximately 60 feet from the Guardsmen and was wounded in the left ankle. John Cleary was over 100 feet from the Guardsmen when he was hit in the upper left chest. Alan Canfora was 225 feet from the Guard and was struck in the right wrist. Dean Kahler was the most seriously wounded of the nine students. He was struck in the small of his back from approximately 300 feet and was permanently paralyzed from the waist down. Douglas Wrentmore was wounded in the right knee from a distance of 330 feet. James Russell was struck in the right thigh and right forehead at a distance of 375 feet. Robert Stamps was almost 500 feet from the line of fire when he was wounded in the right buttock. Donald Mackenzie was the student the farthest from the Guardsmen at a distance of almost 750 feet when he was hit in the neck. WHY DID THE GUARDSMEN FIRE? The most important question associated with the events of May 4 is why did members of the Guard fire into a crowd of unarmed students? | |||

|

|

|

When I was drafted during the Vietnam War, I had a dog whom I loved very much. I could look into his eyes and see the essence of God. Not a personification of some deity, but the force of life which dwells within the animate body. He was not unique, but he was close to me and I recognized the worth of his being.

That morning, the morning I was to report to induction, two eagles flew out of the West and circled over The Land above me. They then returned to the West. I did not flatter myself as an animist at the time, yet their visit wrought a profound effect upon me. I had been searching - desperately searching - for a reason - a justification - to go kill, but I had not found it. To me it was nonsense. I took the meaning of the eagles' visit to be the essence of God, saying to me, "Do not compromise those things which you know in your heart to be true."

My dog came to me and sat. I looked deep into his eyes. There was another universe there within him, as there is within all living creatures. Deep within the eyes of life it shines in triumph over inanimate stasis. And it begged me to stay. To love. To be. To be there, with him. It was right. And I knew then what I must do. I must stay. I must be. I must love. In my dog's eyes shined the light of God. It was a simple choice.

"I shall return tomorrow," I told him.

|

|

|

On the bus, I asked the others to be true to themselves. Two joined me and refused to step over the white line. Scores of others gave themselves and their souls into the hands of the corporate killers. The FBI was outraged that I would not participate in the slaughter. They kept me for a day. They sent me to a psychiatrist and he asked me why.

I explained.

I must stay. I must be. I must love.

My dog held the essence of God, and his simple request was sufficient.

They held no power over me. Then they set me free.

June 1970

If one ponders on objects of the sense,

there springs attraction;

From attraction grows desire;

Desire flames to fierce passion;

Passion breeds recklessness.

Then the memory, all betrayed,

lets noble purpose go and saps the mind,

Until purpose, mind and man are all undone.

-- The Gita

June 25, 1970 Thursday Mountain House, Palo Alto

Cindy, Bruce and I have entered the Institute for the Study of Nonviolence. Joan Baez founded it. It has three or four different locations. The Lytton Street house on Lytton Street. is the yet unfinished Center. We laid cobblestones in the driveway for a couple of days. The Land is where the sessions are held. We stayed there two days, starting last thursday. Here at Mountain House, most of the other sessions are held. We have been working on it for the last few days.

July 9, 1970 Thursday

Sometimes I wonder if it's all real: the evil, the horror, the destruction my ancestors have wrought. Could God, in his game of change, have taken his innocent essence from the Atman and placed it in my body - and I'm watching a movie for my own benefit? And I exist not only to learn from the incredible trip Babylon presents to me - but to act. To write my own script in such a way that I make a decision and act on it. A puzzle. A maze of infinitely intricate pathways. To find the cheese is to make my dream from the nightmare. But all the evil merely being the contrast the fantasy must present to me to create the need for a decision...

Silly, though... It's real. Too real. Then again, acid says it's not. Pot says appreciate it but enjoy it. And check your mortality, kid.

Che's retching phlem. Sally came down with distemper. Could Che get it? She's doing the same thing. He didn't shiver in his sleep last night, though. Christ, I'm hard inside. I could make it through Che's death. I'd hate it but I'd make it.

Cindy wrote me a letter. She expressed her concern over my depression. Said I needed to "share some of that blasted affection I give Che with some nice girl who could return it in many other ways besides slobber."

I freaked out and wrote her a long letter. I told her that I'd have to find the right girl. A special girl. That everytime I felt genuine love, it vanished from me."Besides, I've got a future to change, with no time to give that special girl all the love I'd be inclined to give her." Also, that I probably set my standards too high, anyway. I ended it with, "Flow on. I love you."

I had no right to do that, I know. It wasn't fair to Bruce. All I can say in defense was that I was on an honest rap, thought it out and did it anyway. Once you write something, you can rationalize and say that since it's written in ink, you can't erase it, and that's that.

She must mean a lot to me for me to have said that.

I asked Dick if he'd like to go back east in my truck a few days ago. He accepted. But my transmission fucked up going down a steep San Francisco hill when eight of us went to see "Traffic" at the Fillmore West. It's half out, now, parked in front of the Mountain House. They want $75 for a guaranteed rebuilt. Fuck that. There's a '38 truck abandoned at The Land. I'll check it out.

We're going to tour quite a few of the major peace centers across the U.S. Bruce and Denise are going, too. Denise likes me. She's nice.

Bruce and I made $20 at Stanford, singing and rapping to people. Hitching back, a van going the other way pulled a "U" and the guy asked Bruce to sing him a song. He did 3 or 4 and earned "high 5's" from the driver. One really far out dude, super concern radiating from his eyes, gave us $10 when we told him what it was for. He was really interested in the Institute, too.

| Bruce and Riddle Sis at the Long House in 1970 Photo: ML Rocha used by permission |

July 15, 1970

A couple days ago, Bruce returned from Santa Cruze in a Blue Volvo with a 76 Union credit card. He's always managing to do something like that. It turned out that he had been hitchhiking on Skyline Drive when the people who had picked him up stopped to help at an accident. No one was hurt so he started playing his guitar. Can you see him playing angry protest songs to a group of OH-MY-GOD-I-WRECKED-THE-VAN! people? A chick stopped to put out some flares. Bruce saw a guitar in her truck and it led on from there.

I heard about her for the first time when Bruce asked me to go back to Santa Cruz with him and turn her on to the Military-Industrial-Political-Union_University Complex ("MIPUUC - Me puke!") He said she was a 30-year-old school teacher who was really interested and didn't know anything.

Of course, I went.

I asked Bruce if she was good looking and he said, Yeah!" He always does, so imagine my surprise when Barbara, this beautiful chick who looked as if she couldn't have been more than 19, reading Siddartha, gets up from a red-toned sofa bed, under a hanging lamp in the corner, and greets us as Bruce walks into her house. Wow. She has a far out voice, too.

We talked all night about the U.S. economy, foreign policy, the military trip and our own lives. When my eyes met hers, they locked on, held by a tiny thread of invisible energy.

We went to Steve Pickering's wedding the next day. He held it in Dick Clark's gigantic wigwam, erected on someone's backyard - he didn't know who. It was far out but I couldn't tell if it blew Barbara's mind or not. Two gallons of Red Mountain Burgandy and many incredible joints later, we left the wigwam to the care of a 15-year-old runaway.

We found Roy beside the road on the way up. He was supposed to be in New York. What a FREAK to see him hitching outside of Santa Cruz! We split to Frank's. Barbara and Kristin left - mutual goodbyes. I felt sad - and that I'd never see her again. But I was too stoned to let it keep me awake.

Bruce, Roy and I hitchhiked back to Palo Alto via Roy's in San Jose. Bruce, Roy and a friend good with a harp went to Stanford to try to make some bread. $7.

I got off at the Mountain House. Barbara was supposed to visit the Mountain House sometime that day or the next. I waited until 10 pm, not really expecting her nor knowing what to do if she came. I finally crashed in my truck. I ran through various fantasies of what I'd do if she drove up. Probably during this surrealistic scheming, she drove up and walked past my truck.

In a dream, a girl I wanted very badly reached out her arms to me and I touched them, running my fingers over them and pulling her closer. Closer...

"Rik?"

"Huh... Eh? Wha...?" Dream fades.

"Rik? Hi." Beautiful chick looking over bucket seat at half-asleep Rik. Far out eyes. Green. Long blond hair. "I slept on the hill last night."

Wow. My mind was expanded and confused. Chaos had set in. I pulled on my pants with trembling hands, thoughts centered around finding a place where I could pull myself together. The Mountain!

We split to the top of the mountain Peter and I had found one night, lost and stoned in total darkness, and rapped and rapped.

She took off her sweater but I kept cool. Nice. Very nice. We found creatures in the clouds. Hers was an eagle. Mine was a skull, glowering down at Lockheed.

July 21, 1970

PENS - People steal pens at the Mountain House. Some people come all the way from Connecticut to steal pens. It's impossible to find a pen to write with because they have all been stolen.

I'm writing this with a stolen pen.

PENCILS - No one steals pencils at the Moountain House. You could store all your pencils everywhere, then come back years later and find them right where you left them. One pencil stayed on the kitchen sink for 5 weeks, Another has been on the hot water heater for 2 years. No one steals pencils. Pencils are free.

MONEY - No one knows how to make money at the Mountain House. They all rely on magic. Sometimes they recycle food. On August 6 or thereabouts, we (4) are going to the beach to make some money. Pacing off a liberated 40-foot square area, we'll start at the middle with a crater and work outward until we have a scale replica of Hiroshima after the bomb. Then we'll sit at our respective corners and wear dark glasses, holding cups in our hands and wearing signs reading "HELP THE BLIND".

We also have plans for a "FAR-OUT BANK OF AMERICA", since there is not one people's bank in this country! We could call it INVESTORS RISK or FIRESIDE THEFT.

July 25, 1970

I have $3.

"Chesire-Puss," she began, rather timidly... "Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?"

"That depends a good deal on where you want to get to," said the cat.

"I don't much care where," said Alice.

Then it doesn't matter which way you go," said the cat.

| September 11, 1970 Reported in CNN NewsStand Vol. 141 No. 23 - June 15, 1998 | |

| The targeted village was believed to be harboring a large group of American G.I.s who had defected to the enemy. The Special Forces unit's job was to kill them. Based in Kontum, South Vietnam, the men involved in Operation Tailwind were known as a SOG team, standing innocuously for Studies and Observations Group. Officially, SOG units didn't exist, but they were America's fiercest warriors, conducting classified "black operations" with unconventional weapons and unusual targets. They did little studying and a lot of fighting. According to SOG veterans, they had no rules of engagement: anything was permissible as long as it was deniable. Their motto, according to Van Buskirk: "Kill them all, and let God sort it out." During its preraid briefing at Kontum, the SOG "hatchet force" was told to kill anyone it encountered. "My orders were, if it's alive, if it breathes oxygen, if it urinates, if it defecates, kill it," says Van Buskirk. In keeping with the compartmentalization of information necessary to protect top-secret missions, only a few of the SOG officers knew the precise target. And very few knew the exact type of gas available for their mission, although the unit was promised anything in the non-nuclear U.S. arsenal it might need to complete the mission. The commandos understood there was an agent commonly known as "sleeping gas" available for last-resort situations; they were aware that the gas caused respiratory distress, sudden vomiting, diarrhea, convulsions and often death. The unit leaders were advised to equip their soldiers with bulky but effective M-17 gas masks before the raid. Several days before the operation began, a small reconnaissance force was dropped into a lush Laotian valley near the town of Chavan. As Jay Graves, a SOG recon-team leader, put it, "We went in, snooped and pooped, moved around." Through a special field telescope, Graves' men spotted the prize--several "roundeyes," Americans, in the village. That report was radioed back, and the recon team was told to "groundhog"--remain silent and in hiding until the hatchet force arrived. The sighting of defectors is confirmed today by Air Force "rat-pack" commando Jim Cathey. "I believed that these were American defectors," he says, "because there was no sign of any restraint. They walked around as though they were a part of the bunch." On Sept. 11 the 16 SOG-team members and about 140 Montagnard tribesmen, who had been hired to fight the communists, were loaded aboard four big Marine helicopters at Dak To, near the border with Laos. The sight of the assault force, which included 12 Cobra helicopter gunships and two backup Marine choppers, alerted Jack Tucker, one of the Marine pilots, that trouble lay ahead. "I saw them walking across the tarmac, loaded down with those grenade clips," he says. "And there were these little bitty Montagnards humping so much stuff. I just went 'Oh, man' and knew we were in for some real deep shit." Tucker and the other pilots had also been equipped with special gas masks to protect against chemical warfare. As soon as the helicopters approached the landing zone near Chavan, they came under heavy fire. "It was a hairy situation from the time we got there, " recalls Jimmy Lucas, a squad leader. "Ground fire on insertion is something you are not supposed to get." The SOG team hit the ground several miles from the targeted base camp and spent the next three days fighting its way toward it. "I feel like in them three days I just cheated death," says Lucas. "We never expected to come out. I didn't." On the third night the commandos hunkered down near the village as the Air Force A-1s "prepped" the target. In the morning the SOG forces attacked. Van Buskirk's platoon led the charge. "I went hi diddle diddle, right up the middle. I was on the offensive," he says. Tossing grenades into the hootches in the village and spraying machine-gun fire ahead, the assault force met little resistance. "It was minimal, nothing like you would expect for the amount of people there," says Craig Schmidt, a fighter in Van Buskirk's platoon. "It was very unusual, kind of eerie." Suddenly Van Buskirk spotted two "longshadows," a name for taller Caucasians. One was sliding down a "spider hole" into the underground-tunnel system beneath the camp. The other was running toward it. "Early 20s. Blond hair. Looks like he was running off a beach in California," remembers Van Buskirk. "Needs a haircut. This is a G.I. Boots on. Not a prisoner. No shackles. Nothing." The lieutenant gave chase but just missed the blond man as he slipped into the tunnel. He shouted down the hole, identifying himself and offering to take the man home. "Fuck you," came the reply. "No, it's fuck you," answered Van Buskirk as he dropped in a white phosphorus grenade, presumably killing both longshadows. The village raid lasted no more than 10 minutes. The body count, according to Captain Eugene McCarley, the officer in charge, was "upwards of 100." Sergeant Mike Hagen says "the majority of the people there were not combat personnel. The few infantry people they had we overran immediately. We basically destroyed everything there." The Montagnards searched the camp for documents and booty. They reported to Hagen and Van Buskirk that there were "beaucoup roundeyes" dead in the hootches. Says Van Buskirk: "A dozen, 15, maybe 20." But the SOG team says no bodies were identified or recovered. With the camp destroyed, spotter planes overhead ordered the SOG unit to the rice paddy where the rescue helicopters would land. As the enemy closed in, the commandos were told to don their "funny faces," the M-17 gas masks. Then came the explosions of the gas canisters. "To me it was more of a very, very light, light fog. It was tasteless, odorless, you could barely see it, " recalls Hagen. The gas spread toward the Americans even though the downwash of the chopper blades was pushing it away. Some of the gas masks had been damaged in the four-day battle, some had been discarded, and some were too big for the diminutive Montagnards. "Everything got sticky," says squad leader Craig Schmidt. "We turned our sleeves down to cover ourselves as much as possible. It doesn't surprise me in the slightest bit that it was nerve gas. It worked too well." Some of the Americans began vomiting violently. Today Hagen suffers from creeping paralysis in his extremities, which his doctor diagnoses as nerve-gas damage. "Nerve gas," says Hagen, "the government don't want it called that. They want to call it incapacitating agent or some other form. But it was nerve gas." As many as 60 of the Montagnards died in Operation Tailwind, but all 16 Americans got out alive, although every one of them suffered some wounds. Van Buskirk and McCarley earned the Silver Star for valor. Van Buskirk personally briefed General Creighton Abrams, the top U.S. commander in Vietnam, on the mission. But when the lieutenant wrote his after-action report, a superior officer, now deceased, advised him to delete the part about dropping the white phosphorus grenade--a "willy pete," in Army lingo--on the American defectors in the tunnel. Confirming the use of sarin, Moorer says the gas was "by and large available" for high-risk search-and-rescue missions. Sources contacted by NewsStand: CNN & TIME report that GB was employed in more than 20 missions to rescue downed pilots in Laos and North Vietnam. Concludes Moorer: "This is a much bigger operation than you realize." Melvin Laird, Secretary of Defense at the time of Operation Tailwind, says he has no specific recollection of GB being used, but adds, "I do not dispute what Admiral Moorer has to say on this matter." And the admiral points out that any use of nerve gas would have had approval from the Nixon national-security team in Washington. Henry Kissinger, National Security Adviser at the time, declined to comment. As for the defectors and the policy of killing them, Major General John Singlaub, U.S.A. (ret.), a former SOG commander, confirms what was the unwritten SOG doctrine in effect at the time: "It may be more important to your survival to kill the defector than to kill the Vietnamese or Russian." The defectors' knowledge of U.S. communications and tactics "can be damaging," he explains. "There were more defectors than people realize," says a SOG veteran at Fort Bragg. No definitive number of Americans who went over to the enemy is available, but Moorer indicated there were scores. Another SOG veteran put the number at close to 300. The Pentagon told NewsStand: CNN & TIME that there were only two known military defectors during the Vietnam War. --Additional reporting by Amy Kasarda, associate produce r for NewsStand, and Jack Smith, senior producer for NewsStand Before broadcast, CNN’s top management gave both Tailwind stories (aired on June 7 and June 14, 1998) and their producers its full backing and support. They then withdrew that support and fired us. These actions have profound and far reaching implications for this kind of difficult and serious journalism. We hope that every thoughtful journalist with an interest in this controversy will take the time to read both the AK Report and this response in full before coming to any conclusions. APRIL OLIVER is a producer for NewsStand, and PETER ARNETT Is a CNN international correspondent | |

|

|

|

November 25, 1970 Monterey Pop Festival

Don't really know how I got here. I came with the Institute to act as nonviolent troubleshooters for the concerts. One at 1 pm and the other at 8 pm. Joan, Mimi, Kris Kristoferson and a whole load of really far out Nashville people. I did the whole thing on acid. It was really beautiful.

The heaviest part of the trip was acting as a doorman to the resturant where the entertainers ate. I worked in the kitchen. I met Mimi Farinaat the door. I told her I'd done my college thesis on Richard.

Joan asked me if Che dug kids. All the people were really beautiful.

Judy bummed out on some mescaline. She took it the night after acid. Dumb kid, she has so many personal bad trips happening... I'd really like to help her but the involvement would be very great and I don't think I'm ready for that.

Back at The Land, alive and well Monday night

All my tools got ripped off along with Craig's while we were at the Monterey Pop Festival. But it's all right. I hope they get good use. My car thing is all over.

Craig said he might loan me $25 for a transmission. John, who seems to dig The Land, might loan me the rest. I sure would like to do an Oregon thing in my truck.

Janis Joplin died. OD'd on skag.

Hendrix OD'd on something. We seem to be losing some very heavy people. Jimi Hendrix's death was supposed to have had some dark, mysterous bad happenings about it. He went to a different London hotel than the one he had registered in - with a chick he had never seen before or some other bullshit.

Oatmeal and Brown Rice and Oatmeal Tuesday

There is a 50 lb. bag of oatmeal and a 100 lb. bag of brown rice in the kitchen left over from the last session. We won't starve.

[[Jeffrey+Shurtleff|Jeff]] came over to work on the garden and turned us on to some good hash. I've been mostly stoned on sugar - something I've been doing all my life but never realized.

It's cold in this partitioned-off room in the Long House. I typed up a list of the ripped off tools but couldn't price it. I have an uncontrollable nose drip.

Larry, Bonnie, Howie and Cindy (from St. Louis) came by to see Judy in a rebuilt Morris (Hi, Morris!), all stoned out of their gourds. Judy made a nice organic supper for Eric and us. We sat in the main room until late, reading. I should have asked her if she would like her back rubbed but I conked out like usual.

| Rik and Riddle Sis by the barn at The Land 1970 Photo: ML Rocha used by permission |

November 20, 1970 Friday

Wednesday, I left The Land, hitchhiking down to San Jose. I was trying to reach Standard Transmissions in San Carlos. I was going to sign a work order for a rebuilt Chevrolet four-speed gearbox for my panel truck, my cold, cold immobile home stranded in the trees across the driveway from the Big House.

I caught a ride along with Craig, who was going to the Lytton house with a defense worker, to Wolfe Road. I walked about four miles with my Doberman Che to Stevens Creek Blvd; no one gave me a ride. I got a ride with a group of teenagers to Lawrence Expressway, and that was the last one. I walked and walked and walked into and through San Jose. After all this walking and no ride, I began to think that maybe it was a sign not to get the transmission.

When I came to a glowing time-of-day sign at a car dealer's that read 5:79, I figured that it was the last straw on the sign-recognizer's back, and split across the road with Che and started hitching the other way. Within three or four minutes, a dude picked me up and gave me a ride to some street that led to 280. I walked across the intersection.

As I crossed the street, I thumbed a head driving an orange Subaru 360 with a ecology flag painted on his roof. The back seat was full of things so Che sat on my lap. Try it sometime. When Che lays down, he's longer than that car is wide. We got out at an onramp. Che started freaking out in the ice plants looking for "beggers" He didn't find any, but he was sure they were there, somewhere.

A weird guy in a Plymouth day-glow green Roadrunner stopped. The inside was all custom covered. Che sat on the floor. I was afraid he was going to scratch it and bum the guy out. He took us to Lawrence Expressway, and we walked to the next onramp to 280 on Stevens Creek. Three rides and I'd gotten to where I'd started walking hours ago. Che started chasing the invisible beggers in the ice plants again. I watched helicopters and the like fly into Moffett Field and went through an unpleasant flashback of a night I'd spent hitch-hiking out of San Jose going south. Five hours...

I kicked an ice plant, and Che decided my foot was a begger, and pounced on it. Grabbing my foot in his mouth and shaking it, he pulled me over. This was freaking out some of the wonderfully nice people who kept driving by, so we did it for a while. I acted like I was being attacked. All the people going by were thinking, I bet, "My, what a stupid hippy; allowing himself to be attacked by a fierce Doberman Pinscher. Serves him right."

Then these two chicks in a new Camaro stopped. It was quite unusual, to say the least, but I'm not one to complain, so we got in. I looked at the passenger first. Young and blond. Made me think of my one-time girl friend Chris, in a way. Then the driver. That was a different story. This chick was really far-out. She had a perfectly beautiful face. She wore rimless granny glasses and had her long brown hair in a ponytail behind her. She asked me if I went to school.

"No," I said, "I've been working with Joan Baez's Institute for the Study of Non-Violence for the last few months. She thought that was far out, and I thought she was far out. She stopped at a friend's. There wasn't anybody there. She had on a long overcoat and high heels. She'd broken her ankle somehow. A really fine-looking chick. She had class. She said that she would take me to Steve's. She works at a gas station on Homestead - a Gulf station. She told me to drop by and see her some time there. I asked her if she was attached to anyone as I got out.

"Can I get a number?" I asked.

"Sure," she said.

"I have a memory," I said.

Her name is Sandy.

[File:http://www.arthurmag.com/magpie/wp-content/uploads/2007/10/untitled-1.jpg external image untitled-1.jpg]

December 10, 1970 Monday

Yesterday I drove the '61 Corvair that Dick Donavon gave me back up to San Francisco and picked up 200 copies of RAGS magazine. If I can find places down south that will sell them, I'll make up to $20 a month. At any rate, I don't think I can lose. The only problem is that I'm almost completely broke. I don't have enough gas money to drive south.

Yesterday was work day for the Institute here at The Land. I met a chick I like named Janis whom I've never seen before, even though she'd been with the Institute about a year. She had a silver wedding band on her finger. She said she had done some work with the farmworkers in Delano. I found her some coffee. I wish I wasn't such an introvert. Maybe I'll see her tonight at the pot luck dinner at the Lytton House.

Reggie, an AWOL Army medic is staying here. He pawned off his stereo in San Francisco today. He says he has killed a lot of men in Vietnam.

"We shot two civilians once. We didn't know they were civilians at the time. We were given orders to shoot anything that moved after a certain hour. Afterwards, to keep from getting in trouble, we placed gernades on the bodies to make them look like the enemy."

He'd been wounded by an M16 - our side - which had broken his femur. He said abiout 50-percent of the wounded were from mistakes from our own side. He had spent six weeks in a Japanese hospital in traction before they had shipped him back to Ft. Browning.

February 17, 1971 Thursday

I didn't work today. Went to the Bhuddist Zendo in Las Altos with Larry, Craig, Reggie, Judy and Carrie, Bill Garaway and Karen. Ate. Rapped with some militant people. We split to hear William Kunstler speak at St. Ann's church. He spoke at the alter about the Berrigan case.He related this trial to the trials in Germany in 1933.

|

|

|

March 6, 1971

I just got through doing a Volkswagen engine swap today. I had talked a guy into giving his fucked-up '62 VW to the Institute Community so that we could use it for parts. I towed it up from San Jose to The Land with a chain this morning. We have another fucked-up VW up here but the engine is fairly good in it so we decided to swap the good engine into the '62 and give it to Lee and Carol to use for transportation on the flatlands.

Lee and Carol and Will and Janis and Leah, who just had a baby girl, and her husband, Elmont, who will be sentenced this month for draft refusal, have started a land trust in East Palo Alto, the black community - renamed Nairobi by the people who live there. The way it works is that the land and the house they live in are bought, not rented, over a ten year period. This way the land is never resold, but rather recycled among people in the Institute Community who need housing. It is essentially taken off the market - taken off the capitalist merry-go-round of buy and sell and buy and sell.

A really incredible thing is starting to happen up here. It's called Draft Refusers Support. It's the middle class community getting themselves behind supporting draft resistors. I couldn't believe it when I went to the first meeting. Resistors never used to get that kind of support from the community.

Chris Jones, who just got out of Safford Prison and has just moved into the attic, showed a color film he had taken inside with a smuggled camera to all these people.

On saturday or sunday nights I go over to Struggle Mountain and play chess with Robert Stagey. He owns that big green flatbed truck that wasn't running but we finally got it running with the help of my truck's battery. He and his wife Christie and little Gabriel came up for dinner tonight. We had sauteed zuccini squash and bean sprouts over boiled bulgar wheat with butter and Tamari soy sauce (aged two years). Also a good salad. We are now a full-fledged commune. Communes are illegal in Palo Alto, but since illeagle is a sick bird, we don't have to worry about it.

Yoga is really far out. We have a couple of people who are really into it: Bill Garaway and his chick Karen, who can tell incredible stories. They are building a treehouse across the road to live in. Squatting. Bill did over a year in prison for resistance.He says that all the heaviest Yogis are coming over here to America because their most serious students are not from India or Europe but from the white middle class of the United States. I heard one talk at Golden Gate Park last summer. He said that the white middle class finally had what civilization had worked thousands of years for, materialistic fulfillment, and now they had the choice to either take it or turn away and say it wasn't worth shit. I'd like to get more deeply into yoga but I'd only succeed with more disipline than I have now.

I left Che outside a bookshop yesterday. I was watching him from inside, through the storefront window, when a little kid, not much more than a toddler, maybe two years old, no parents to be seen, walked up to him as he was laying down, waiting for me to return, and started petting his head. Che didn't like it. Before I could do anything, he swung his head at this little kid and seemed to bite him on his face. This totally freaked me out and I ran outside to see how badly he was hurt - really scared for the little kid, for Che and for me. Was I surprised to find that Che hadn't bitten the child at all but rather knocked the brat away, sprawling him on his ass with a swing of his big snout! He seems to understand the fragility of children. One far out dog, huh?

|

We had gotten a ride to the black section of Palo Alto. We all climbed out of the truck and there in front of us were about 10 or 12 negro children - their eyes all bugged out at Che. "Does that dog bite?" one girl asked, standing with the rest about 20 feet away, quite apprehensive. "Only on Tuesdays and Thursdays," I replied, bending over to raise his lips and show them his big teeth. Their mouths all gaped. "What's today?" "It's Tuesday!" one little boy shouted - and they all turned in unison and ran down the street in blind terror, screaming at the top of their lungs. "He's only a puppy," I cried. But they didn't hear. |

March 22, 1971 Monday

I am standing at the streetlight near US 280 on Page Mill Road. Dozens of people driving expensive cars keep passing me by. One dude stopped. His bug reeked of grass.

After maybe an hour, Chris came down off 280 from San Jose and gave me a ride. Chris spent 14 months in Safford Prison for refusing to register when he was 18. He had a really rough experience. He said that all the "hacks" - guards that couldn't quite make it at other federal prisons - are sent to Safford since it is a minimum security prison and the prisoners are less likely to be violent.

March 24, 1971 Induction

The alarm rang about 4:30 A.M. I jumped up, got dressed, walked outside the big house and called Larry in the middle cabin. I opened Judy's door, put my hand on her shoulder.

"Judy, do you want to go?"

"No," was the sleepy reply.

Larry came in. He said that Marian might like to go. I called. her through the open attic door. Larry made us all buttered toast. I packed 125 of the leaflets I had printed on the A.B.Dick 360 into my Hawaiian flight bag. We took Marian' s car, the four-speed Grand Prix. She drove. It was a cold morning and the air was very clear as we drove down the mountain. It had rained earlier, and the lights from the myriad cities that lined the bay and extended below it sparkled brilliantly. Highway 280 was deserted, and in the cold early morning dark, it felt strange to ride this normally crowded six-lane concrete ribbon alone.

Larry knew the way. He had been busted there a few months before for refusing to get off a draft bus when ordered to do so by a policeman.

The Greyhound bus depot was full of young men standing in quiet groups with their families or sitting alone - all with yellow Selective Service envelopes in their hands. Larry, Marian and I split up with an ample supply of leaflets and began talking to people and distributing them. Nearly all the people we approached took one, even those who had enlisted.

I walked up to a dude with shoulder length-blond hair, moustache and scraggly chin. He had a resistance button on the lapel of his coat. I asked him if he was resisting.

"Of course," he said.

Some guys were hugging their girlfriends and didn't have time to read a leaflet or sometimes even take one. Before we expected it, the P.A. system rang out: "Will all Selective Service inductees line up at Gate Two, please."

The crowd moved slowly, sporadically forward. Someone opened the door and they walked outside into the waiting buses. I stood at the rail by the door and handed each guy a leaflet as they walked by. They walked by so fast I couldn't get to them all. I couldn't imagine why they were in such a hurry.

Their girls stood outside, leaning against the rail at the edge of the walkway, some smiling weakly, some biting lower lips and waving. Some just looking - expressionless. Their boyfriends, fiancées and husbands gazed somberly out the bus windows. The scene was affecting them. The strangeness, the alienness - the wrongness - that such a tableau could exist was coming home to them. None smiled but artificial smiles.

"If there is anyone on the bus who does not have an order for induction into the armed forces," the pasty, fat and ugly woman bellowed, "will they please remove themselves from this bus."

'How sick this woman must be,' I thought, 'to work for the Selective Service System.'

She looked as if she had been watching noyhing but television commercials all her life. She waddled to the rear of the bus and began checking induction papers and marking off names.

Across the aisle and out the window, I could see another bus full of kids; a giant sardine can on wheels - fresh meat for the war machine. I strolled off the bus and entered the other one. A younger woman was checking forms at the rear of the bus. I reached over her shoulder and passed leaflets to the guys in the rear seats, then everyone else. I wasn't worried about getting kicked off. After all, I had my induction notice, too. I returned to my bus and as soon as the woman checked my form, I proceeded to leaflet all the fellows in my bus.

We started rolling. Girls waved. Their men returned waves. I watched. Our bus led on Highway 17 north. I knew that I should say something to them, but I was afraid to speak. I've never done much public speaking but as the bus rolled further and further away from San Jose, I felt something inside myself. An anger burning, growing. A disgust so overwhelming that I knew I either had. to speak or throw up because the vibrations I was receiving from the people on this bus were so weird and jumbled.

Suddenly my hand was on the baggage rack and I was standing. Walking. I had run out of excuses. The radio news was over. The sports was on (I didn't want to offend anyone). We weren't passing by any big, noisy trucks. I punched the radio to turn it off. It only changed stations. I punched it again to put the dial in a quiet place between stations.

It played, "and I feel like I've been here before…." Then Steven Stills' voice faded into static.

I asked the driver to turn it down. I had heard him remark earlier to one of the inductees, "Oh, it's not so bad. You do two years, then you're out."

I was afraid he might give me trouble but he ablidged me - and the bus was quiet save for the noise of the wind and the engines and tires rolling. I stood, black leather jacketed, clean shaven in my $20 shirt, arms braced against the luggage racks.

All eyes were on me.

"Your life belongs to you," I said. "Not the weapons manufacturers who created this war. Not to the government who runs it for them. But to you. Your life belongs to you!"

"For God's sake," I said, "don't throw it away."

That's what my leaflets said in big black letters.

YOUR LIFE BELONGS TO YOU.

They listened attentively. Even the jocks. The air was very, very heavy.

No one said anything.

| Rik by MLM |

War is for killing. This I know.

It's evil and my senses tell me so

And as springtime rises up from bitter winter's snow

The seeds of love I sow here

May they grow.

Oh Mother, please protect me from the cold

I fear this world will not let me grow old.

That Killing Floor is calling. Yet may I be so bold

To try to burst the burden of the mold.

Living in darkness isn't right.

We're blind until we drive it from our sight.

But if we sit and only dream of morning's light

We may never make it through the night.

So come on, give your friend a helping hand.

Lift up your head and wipe away the sand.

If you can't see him then, my friend, you stand

Upon the Killing Floor of the damned.

Oh Mother, she once told me as a child,

"Beware this age, my son, for fear runs wild.

The Killing Floor may see all love defiled

And darkness may close in after a while.

No one's ever got through life alive.

The Killing Floor may not let you survive.

But if you refuse evil, let love be your soul's guide,

You'll cross this dark land to the other side."

April 2, 1971 Rattlesnake Pit Morn

The morning is so beautiful out here in the Rattlesnake Pit. This is Che's and my first morning out here. There are twelve panes in the window on the uphill wall. The sun shines through each one until they are all bright. I took Cindy to San Francisco airport yesterday morning. She was a flash. In and out of my life so quickly, I wonder if it even happened...

I was working at the print shop when Al called. The phone was for me. It was Bill Garaway at The Land. He said that a girl had called and would be arriving from Reno at 6:30 at the bus depot down the street.

"Who is she?" I asked.

"I don't know. It was person to person. She didn't say."

"Person to person? To who?"

"You."

"Me?! Jesus Christ. And you don't know who it was?"

So I spent the rest of the day fucking up, trying to figure out who I was going to meet at the bus station. Waiting at the bus station was a trip, too. Weird!

Cindy walked in.

I hugged her, took her bags. We walked to the University on ramp to El Camino and hitched up Page Mill.

We talked in the cold Rattlesnake Pit.

She gave me a book. The Only Revolution by J. Krishnamurti.

[ see Krishnamurti Speaks with Dr. Anderson ]

April 19, 1971

It's really quiet now and there is no one here but me. Che and Oly, the Doberman-Samoyed puppy, are wrestling each other on the living room carpet; Che's mouth envelopes Oly's head and I wonder why he doesn't bite Oly's head off. A fly buzzes against the picture window next to me trying in vain to penetrate the invisible it from somewhere. I summon the royal fly-swatter: "Che!" I say. He looks up from his play. "Bugguses!" I say, pointing to the flies. Che jumps up and chomps them out of the sky, then looks at me, ears up, for something else to vanquish.

An old yellow pickup jounces up the-driveway and stops in back. Two fellows from Black Mountain Commune, our next door neighbors, have come to place their weekly order in our organic food cooperative. Black Mountain is a dome commune. The people who live there live in geodesic domes in the forest.

| Rik filling Co-op produce order Photo: ML Rocha used by permission |

Tomorrow, I'll drive my panel truck up to the farmer's markets around San Francisco and buy enough poison-less bulk organic vegetables to keep our communities, totaling nearly 100 people, supplied with fresh food for a week at the incredible cost of less than 50 cents per person per day. Try that!

They left, so I sat down and tried to play the guitar a little. It's a very difficult instrument to master, but - wow! - is it spacey! I bought a guitar - a Harptone. The one Ringo Starr likes. Its really nice. Great sound. I wanted to have a good guitar - in case I went to prison. Music is really where it's at.

RATTLESNAKE PIT

I can't talk about my guitar without playing it, so I walked out to the Rattlesnake Pit where I live. The Rattlesnake Pit was a disused water tank last year. Now it is a house with hardwood floors (2 levels), windows, doors, and a shingled roof . The only drawback is that I had to put the doors in the roof because the sides are all concrete. It overlooks a big, wild, forested valley. If I walk up the hill behind it, I can see from San Francisco, jutting out into the bay, to downtown San Jose. Really incredible.

April 26, 1971

Dear Claudia,

Hi. Rik here. Its past midnight but I thought it might be be a good time to write you this letter.

I live in a rattlesnake pit. Bet you didn't know that! And I stood outside the doors on the roof of the rattlesnake pit and looked at the sky. I couldn't see the Milky Way because the glow of the city on the other side of the hill obliterated it.

"God," I said, "please turn off the city so that I may see the sky."

But the city stayed on.

So I climbed in here, lit my kerosene lamp and took out my notebook to write you a letter. Perhaps you think I'm stoned to go and write you a letter after midnight when I have to go to court early the next morning and then to ugh-work. But I'm not. I'm 100% straight.

I'm writing you this late because I can't sleep until this letter is done. I've seen you all day. In my mind's eye, I've seen you walking across the polo grounds in Golden Gate Park and standing on the hill of the gun emplacements overlooking the bay. Recurring images, again and again.

It was so hard today to work at the print shop. The copies would shoot out of the press and mesmerize me into seeing your face, and I'd have to snap myself out of it or ruin the run. I wanted to be somewhere, anywhere except the print shop, with you.

April 28, 1971

Hi Peg,

What's up? I thought I'd write you a letter this morning before I went to work. I just woke up. It's foggy outside the giant open air window of the Rattlesnake Pit, and a little cold. But I'm warm because I have lots of blankets over me.

Che woke me up by walking around on the roof. I spent many weekends shingling and building the roof. I used old, old shingles from the old swamp houses and now this place looks like its been here a hundred years. Che was mad because I wouldn't let him in the shutters on the roof. He doesn't understand why I wouldn't let him in last night. That's because he's grown accustomed to his smell and I haven't. Last night he routed a skunk from the trees nearby. It sprayed him, and the smell is everywhere.

Ugh! I can still smell it.

Tell Bruce I traded the Moserite guitar for a Martin. I think I like acoustics better, too. Almost everyone up here has started playing guitar, now. Every night we all sit together at dinner (organic vegetarian) and talk about whatever is on our minds.

Bill bought an old psychedelic school bus, that runs on propane, up here the other day. We are going to take it to a draft board next week from the Greyhound station where everyone gets ripped off. We'll serve tea and cookies to anyone who wants to follow the regular busses up and give our draft raps besides. It was my idea, so I get to pay the gas.

I got my truck running the other day. It runs like a top. Took it down to get it registered. On the way back up from work, I got pulled over by The Man. I gave him my draft resistance rap and he let me go, even though only one headlight worked, period.

Did you get the leaflets? The demonstration was kina heavy. We could look in back of us for about a mile and the street was filled with people. The polo field at Golden Gate Park had more people than I have ever seen.. La Raza, a militant Chicano group, seized the stage before Dave Harris could speak. They called everyone (all 200,000) "motherfucking honkies" and brought up the POW issue. They must really be gullible to swallow that Establishment rhetoric, since the POW thing is used as a political ploy (it was used to extend the Korean War, too.) A hundred thousand people walked out as they had the stage for more than an hour. Everyone booed. Ever hear 200,000 people boo at the same time? Heavy.

Gotta go. Work is a drag but it is a must. Need shocks for truck.

April 27, 1971 Big House

Incredible things have happened since I started this letter. The food conspiracy, for one, has jumped from 100 to 400 people. I just got back, from a grain run to the City (S.F.) with Che in my truck. I spent nearly 400 dollars at a dry goods warehouse. A girl from the FLYING SAUCER INFORMATION AGENCY turned us on to 150 pounds of avocadoes for $5. We sold them at 50 cents a pound.

All day I've been hungry for a dried banana, since I've never had one. (How do they dry bananas?) I didn't eat anything except garlic cloves, though, since I'm on a garlic fast. Nothing but garlic and seed-bearing fruit juice. It really gets me high.

Garlic is a very incredible plant, although I I've never heard it praised by the AMA (American Murder Association). I had this incredible cold with runny nose and sneezing over and over, uncontrollably. I skipped dinner (never eat when you are sick) and ate a few cloves of garlic and three hits of vitamin C. Yesterday morning it was gone, only 12 hours later. Garlic's been used to cure many aliments by many cultures for over 5000 years. It seems to me that if it didn't work, they would have stopped using it.

hi peg

rik here + che-droggie. got your letter.

i've been in the mountains with che dozens of miles from roads and people. not from smog, tho, it seems to be everywhere except places over south pacific, i hear.

sad news: hitched to lobos state reserve last month to try and get some info on the mysterious sea-lion deaths happening just north and south and all over. semi-paralyzed sea lions floating onto shore and being eat by sharks because too weak to swim. why? didn't know.

Decided 2 ask someone who's job it was to know - ranger rick. he didn't know. what's worse, he'd not even heard about it. this was be4 the papers heard about it. Now it's worse because boats are running into sea lion corpses up and down the coast. found out why, finally: around this summer the maximum "safe" level of DDT concentration in salable government-inspected meat was 7 parts per million. A research team did a national study of dead (accidental) people's corpses to ascertain the DDT concentration in the average u.s. person's body. it was 14 parts per million. now, get this, a team from, i think, stanford university (would be associated with Dr. Paul Ulrlch) analyzed the sea lion corpses for DDT concentrations and found (ya find this figure in the papers, I bet) that they contained tree thousand, nine hundred parts per million.

I find life very good for my head, how about you?

Everyone says that my way of life is the way of a simpleton.

Being largely the way of a simpleton is what makes it worth while.

If it were not the way of a simpleton

It would long ago have been worthless,

These possessions of a simpleton being the three I choose

And cherish:

To care,

To be fair,

To be humble.

When a man cares, he is unafraid.

When he is fair, he leaves enough for others.

When he is humble, he can grow;

Whereas if, like the men of today, he be bold without caring,

Self indulgent without sharing,

Self-important without shame,

He is dead.

The invincible shield

Of caring

Is a weapon from the sky

against being dead.

-- Lao Tzu

A letter from Peg that I received the 14th of May, 1971

Dear Rik and Che,

High! What's happening? Its about time I wrote you a letter. I sure am a creep! Wow! You're terrific!! Where shall I start?

Oh Yea! I saw you on T.V. What a coincidence! I was up seeing Mom and Dad. We were talking (Dad was watching the T.V., of course, while reading the paper and so forth) anyway -- the news came on and showed blocks and blocks of people and I said, "That's where Rik is!"

Suddenly you appeared on the screen. I started screaming and shouting "There's Rik!" I was so excited! I'm so proud of you. I probably brag about you too much, but you are what you are and that's "good!"

O.K. No. 1 - The anti war March leaflets - oops! - posters, I posted them all over the college. The U.P. of the student body (I gave him a whole bunch) passed them out to all the high schools. They were everywhere. The custodians took them off. So I tricked them and posted them everywhere the next morning with masking tape. Everyone knew about the March. Several people went to San Francisco. They brought back buttons and peace treaties.

About this time I got your peace treaties (which were better cause they were more detailed). At the moratorium we passed them around and even drew lines on the back for more signatures. Several Vets, spoke on loud speakers against the war then laid their medals on a coffin with a flag dropped on it. It was together. We all sang songs and talked and planned. I wish you could have come to speak because we need someone like you to really tell the people about the movement. Later on we had a big vegetable stew and talked and passed out leaflets he got in S.F. at the march.

We planned a march on the federal building and hoped for two-hundred people. Night before it was to start, two investigators came to David's house and questioned him. It really freaked him out and a lot of people, too, cause only 15 people showed up the next day for the March.

The new things you sent me are being circulated throughout B.C. Its so nice to receive information. David put your treaties with his and wrote a letter and sent them to the Center. He was really excited about it, so I let him send them directly to a center, instead of to you first. I hope it was ok.

Gee -- Its really hard to find time for everything. I'm beginning to understand why its so hard to attend school and be an anti-war protester at the same time, but I'm trying my best!

I LOVE YOU, please take care! Tell that old "skunk chaser" to take a bath in tomato juice. Give him hugs & kisses from me! You too!

Love you both, Peggy

MAD BABYLON

by Rik

My love has flown far from here.

I may not struggle on

Now that she's gone.

I read my legend in the mirror.

It said I couldn't smile

Or frown. So long.

You taught us "right" through all your wrongs.

You measured love with diamond rings.

You taught us fear and who to bomb.

"Mad Babylon - the Golden Whore!" we sing.

We must have thought a lot of you.

We let you chain our lives without a fuss.

You must have thought us simple fools

To try to take that sacred part from us.

You taught us "right" through all your wrongs.

You measured worth by tone of skin.

To use your toys, we'd work so long.

"Mad Babylon - the Golden Whore!" we sing.

The table's turning, Babylon,

The rules you've made, the games you've played are through.

How can we thank you, Babylon,

When hate and wealth and war were all you knew?

You've killed a half a billion friends

In over half a dozen wars.

You worship gold and buy your dead.

"Mad Babylon - the Golden Whore!" we sing.

My love is in a distant land.

She knows that I am coming; won't be long.

I etched my saga in the sand.

The tide rolled in.

The seasons changed.

I'm gone.

THE MAN FROM ANIMAL LIB

Copyright 1971 Rik Masters

Liberation Press

Palo Alto

California, USA

I

The eyes glinted in the darkness as they examined the lonely hillside from behind a clump of brush. After searching carefully for movement, a shape appeared in the moonlight . A withered, hunchbacked silhouette moved joggedly, erratically up the hill, grasping something sharp and glistening in its hand.

The bees waited silently in their hives. There was an aura of tenseness in the air. Worker bees, slowed by the night chill, vibrated their wings to express their uneasiness. The queen was hyper-aware, unconscious of the drones mulling about her, all her senses keyed in on the approaching form.

Leaves rattled in the branches of the trees as the wind rose. A whirlwind scooped up a bushel of leaves and, swirling madly, dissolved at the edge of the forest. A cloud skimmed low between land and moon. It's shadow engulfed the hillside.

The hives were cast into black shapes by the cloud. The hunchbacked thing found them, rose to its full height, and swung the blade in an arc over its head, jamming the point between the top lid and the side of the first hive. With a downward motion of its arm, the hunchback popped off the lid. Out fled a swarm of confused and astounded bees.

"You're free!" the hunchbacked thing cried in a wretched, hoarse howl. "Free!"

It raised its arms, one shorter than the other, to the sky in a gesture of freedom. The bees buzzed madly in circles around him. Then their confusion was over-ridden by a sudden euphoria. All fear was quelled and joy took its place.

"Freeeee!" buzzed a bee. Another took up the cry. "Freeeee!"

They were joined by others as more lids were pried from neighboring hives. Dancing wildly on fluid currents of air, they let themselves be carried by the wind, sometimes colliding drunkenly with each other, but never ceasing their cry of "Freeeee!"

Suddenly the moon shown through the clouds, illuminating The Land. All was silent. The bees were gone. The hives were empty. The hillside was deserted.

In the forest, the trees trembled.

II

Jeffery was aghast. His eyes relayed total noncomprehension.

"They're gone. They're all gone," he said to Judy as they stood in the kitchen hallway. "Every one of them! It's incredible. Somebody stole them. They must have stole them. All the tops were ripped off the supers. They stole the bees! But they left the honey..."

"Hmm," hmmed Judy. "That's all very interesting. But how the fuck do you steal bees?"

"Maybe they used a vacuum cleaner," said little Carrie to her mother as she spilled her applesauce on the floor.

"I just can't understand why anyone would do a thing like that. It doesn't make sense!" exclaimed Jeffery, bugging his eyes and pouting.

Just then, Rik walked in, grabbed a cereal bowl from the shelf and filled it with puffed rice. Noticing Jeffery's pout, he asked, "What's wrong?"

"Somebody stole his bees," replied Judy.

"With a vacuum cleaner!" cried Carrie.

"With a vacuum cleaner?" asked Rik, amazed.

Jeffery shrugged. He looked about to cry.

"You just walked over this morning and the hives were gone, right?"

Jeffery shook his head. "They didn't take the hives. They just took the bees."

"What? That's impossible. You can't take just the bees and not the hives!"

Jeffery nodded. Judy shrugged.

Carrie said, "You could do it with a vacuum cleaner, Rik!"

The tomatoes were starting to turn orange, still speckled with spots of green. Karen plucked a weed from the tomatoes' earthen row. Next to her, Bill hoed in a freshly turned square of earth, silent and content in garden meditation.

"Did you hear, Bill," began Karen, breaking the easy silence, "that somebody stole Jeffery's bees?"

Back came Bill's mind from timeless suspension in the Atman to the puzzling world of reality, which, he knew, was an illusion. His gaze traveled from the garden, slowly up the hill, and stopped at the row of five white bee hives.

"Someone stole Jeffery's bees, you say?"

"That's right. Every single one of them."

"But they didn't take the hives!"

"No... Its all very strange."

Jeffery gazed out the window of his house into the forest below. But the peaceful scene could not calm his troubled mind. He was thinking about his bees. The bees he had raised from tiny larvae. He had nursed them through the wet, cold winter months with gallons of sweet sugar water. He had moved the hives halfway up the hill to allow them to be warmed by direct winter sunlight. He had felt a kinship with them. And he had believed perhaps they had felt the same toward him. After all, they had never stung him even when he took their honey.

How wrong , how senseless, for someone to take them from him!

What would become of them? Would they be given a new home? Maybe, heaven forbid, empty hives, miles from the nearest flower! Or worse yet - and he hated to think of this, although it seemed the most likely given the odd circumstances - chocolate covered honeybees!